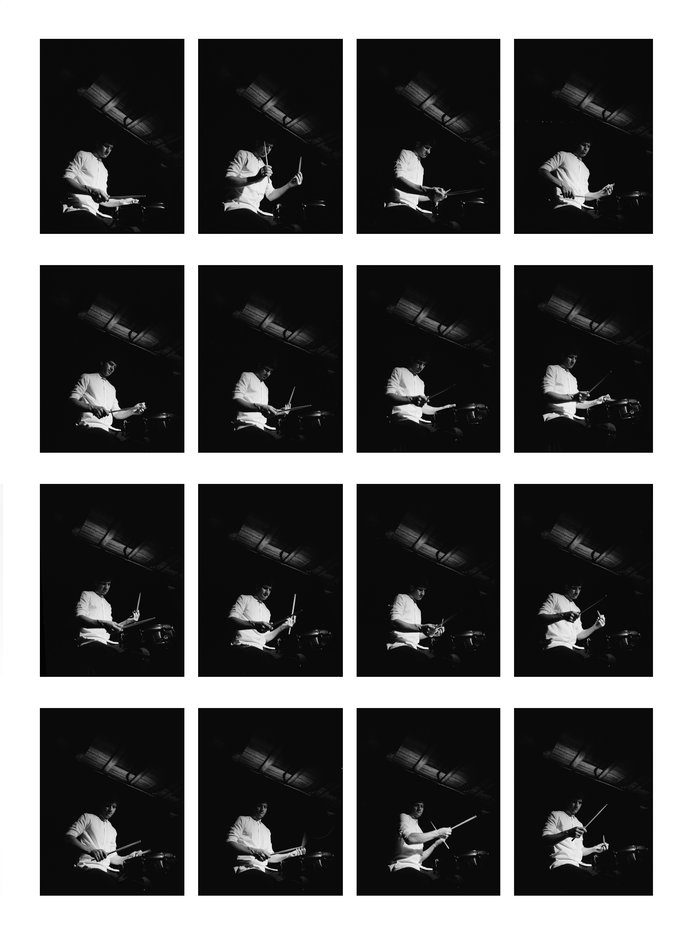

ELI KESZLER!

ph Edward Brudzinski

Eli Keszler is a New York based artist, composer, and percussionist. Kessler’s sound installations, music and visual work have appeared at Lincoln center, MIT list center, and the Victoria and Albert museum amongst many notable others.

In performance, he often plays drums, bowed crotales and guitar in conjunction with his installations. In his ensemble compositions, he uses extended strings, motors, crotales, horns and mechanical devices to create his sound, balancing intense harmonic formations with acoustic sustain, fast jarring rhythm, mechanical propulsion, dense textures and detailed visual presentations.

‘We all are deeply effected by the environments we inhabit.’

While drums might be home base for Keszler, they certainly don’t limit his exploration of sound and the spaces it reflects. Using diagrammatic scores to birth the sound, Keszler finds that the unexpected obstacles and spontaneity of reality shapes his installations in ways he could never predict. Having created projects on his own label REL, Keszler has also had work released by ESP-Disk and has appeared at Eyebeam in NYC and the Boston Center for the Arts.

Eli’s work is seemingly defined by ‘mistake, circumstance and observation’. He senses the unseen in the environment, ‘I don’t feel the need to impose a lot of my own ideas on top of things. I rather like to reveal environments from the surface of a space or instrumentation’.

‘Ideas are quick, and its important to keep them like a spark’

Keszler had been experimenting with various projects and had begun to think of composing, as a way of defining space and environment, which naturally led to installation. Eli does not separate the two forms, considering all improvisational approaches to be forms of composition.

His first installation project was Cold Pin from 2011 before the notable, Breaker NEUM piece, in 2013, which was installed at the south London gallery and detailed the manner with which installations connect to notations.

ph Edward Brudzinski

‘I was imagining the installation defining a space which induces specific types of performance and listening as you move through the space’

Keszler’s evolving ideas have led to being influenced by a space relatively new to him: the dancefloor. He recently played some shows on the European club circuit, thanks to Bill Kouligas, whose Berlin-based PAN label released Catching Net. Using acoustic instruments in rooms with powerful sound systems changed how he thought about filling spaces with sound. «It started to affect and define my music,» he recalls. «It connected to the roots of a lot of my installation projects.»

After reevaluating what type of record he wanted to make, and record following collaborations with the likes of Helm, Oren Ambarchi, Keith Fullerton Whitman and Rashad Becker (who mixed the album) ‘Last Signs of Speed’ is Keszler’s first solo release since 2012’s Catching Net and media reviews have been complimentary with ‘Fact magazine describing the album being filled with ‘surreal rhythms and transporting drones.’

‘I had to figure out why I wanted to produce a record when I’ve been so active working in installation, performance and visual art.’

The album displays a clear clarity allowing the listener to focus on individual sounds and infer connections between them. Perhaps Keszler’s affinity for spaciousness comes from his many collaborations. Over the course of his career, he has played with a wide range of experimental musicians, including minimalist pioneer Phill Niblock, guitar iconoclast Loren Connors, and sax legend Joe McPhee.

‘I just responded to what was in the air and this music formed itself to a large degree.’

The week of the album release Keszler performed a free concert at Boston City Hall. He had been commissioned to create art for Boston City Hall, a six-floor building in which each story houses a different part of the government. The stark, Brutalist setting of the City Hall is a fitting location for Keszler’s alternately dreamy and anxious soundscapes.

‘Boston has had a complicated relationship with this building and this is fascinating about it. I want to build a piece about this complexity.’

Keszler recorded sounds from the outside of the building, and streamed them through wires intertwined inside. «I’m trying to expand the building without using any cement, basically.»It’s yet another way that his unique talents can make space a part of his art. That relationship seems to guide his entire approach to sound-making, even when it’s not part of an installation.

I recently communicated with Eli, via email to emphatically engage in distinct depth about his rich and rapid achievements in art, the Boston installation show; plus, frequent collaborations and what inspires his ever evolving artistic pursuit.

Edward Brudzinski

What influenced your work to be all about spaces?

We all are deeply effected by the environments we inhabit. Social communities, architecture and technological are discrete space, and I treat these spaces differently when working within each of them.

When did you begin focusing upon ideas of installations?

My first installation project was Cold Pin from 2011. I had been experimenting with various projects before this time though and had begun to think of composing as a way of defining space and environment which naturally led to installation.

Could you explain the ideas, concepts behind your installation, Breaker NEUM and how does this installation differ from the others, as all your installations not only force musical ideas to interact with an acoustic environment but, in turn, for flesh-and-bone musicians to interact with both of them..

Breaker NEUM was a piece installed at the South London Gallery. Neume’s are a form of notation used in plainchant. I was thinking of the way these installations connect to notation. Their forms were defined through drawing, similar to notations connection with performance in conventional composition. Rather than notation defining the actions of a single player that then performs a work, I was imagining the installation defining a space which induces specific types of performance and listening as you move through the space — functioning as a type of notation.

You are a solo artist yet, have collaborated positively with cool artists, such as Tony Conrad, Oren Ambarchi, Jandek, Loren Connors and the Icelandic Symphony Orchestra. What do you enjoy most about collaborations, compared to solo creativity?

The social aspect, conversations, all of it really. I enjoy working through ideas that I wouldn’t on my own, it opens up my work in various ways through this.

«I like to work with raw material, simple sounds, primitive or very old sounds.» Why is that?

To me technologies have a temporal aspect to them – they are insignias of a certain historical moment. But a piece of wood falling, or metal against metal are ancient, and timeless to a degree. They tap into a certain part of us that goes way beyond our taste, or this specific moment..

Edward Brudzinski

Do you feel that there are any differences between composing and improvisation?

I don’t separate the two forms in this way. I consider all improvisational approaches to be forms of composition. To me the cultural spaces these terms define are significant in that they are built around different types of communities, but at this point the two terms and this supposed divide feels a little unnecessary.

Could you explain what and how the unexpected obstacles and spontaneity of reality shape your installations?

My work is completely defined by mistake, circumstance and observation. I feel mostly that I pull things out that are already in the environment, I don’t feel the need to impose a lot of my own ideas on top of things. I rather like to reveal environments from the surface of a space or instrumentation.

It is four years since, Catching Net with Your latest album, Last Signs of Speed dropping last month. Why did you wait so long?

I had to reevaluate what type of record I wanted to make, I had to figure out why I wanted to produce a record when I’ve been so active working in installation, performance and visual art. Catching Net was a record of installation performance works – really documentation of performances and installation. I wanted to make something that worked within the specificity of recorded music. To try and treat recorded space – and the music distribution system as a type of format for installation in a certain sense.

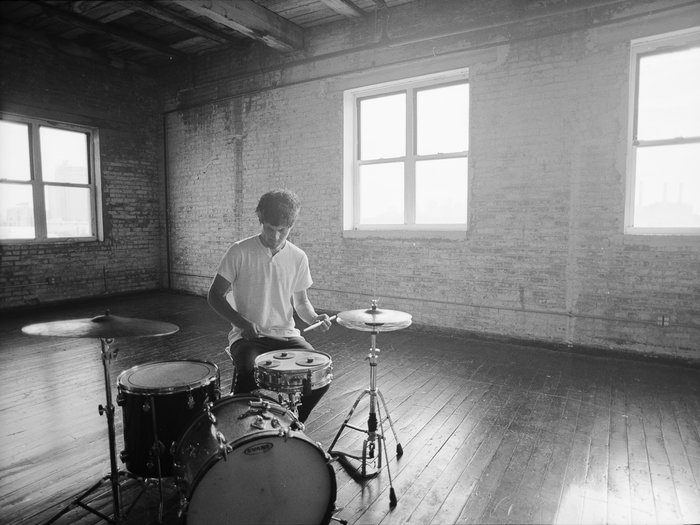

Could you, please describe to our readers the recording process for ‘Last Signs of Speed’?

It was recorded in a studio primarily, solo drums and then with a few instrumentalists and recordings of myself on piano, vibraceleste etc. A pretty simple process ultimately. I spent a lot of time developing drum sounds in the studio. We amplified the drums in the studio – sending the bass drum through a large bass amp to create certain low end effects.

ph Edward Brudzinski

Which album in your catalogue, do you recommend for our readers to listen, who have not previously heard your work?

I would recommend Last Signs of Speed.

Your recent ideas were also influenced by a space relatively new to you: the dance floor, after playing some shows on the European club circuit. How did these shows happen and what inspired you so much?

I would say it is mostly the utilisation of massive club sound systems which are used for electronic music concerts of all kinds in Europe that helped form this record, more then the club circuit which I am not really a part of. Though the frequency range of these sound systems are a huge part of this music. The physicality of these speakers attracted me and changed the way that I approached and played the drums, I just responded to what was in the air and this music formed itself to a large degree.

ph Edward Brudzinski

CONTACT

https://www.facebook.com/elikeszler/

- NEW FRIES! - 08/21/2020

- MR STERILE! - 06/08/2020

- DELILUH! - 01/01/2020

Comentarios recientes